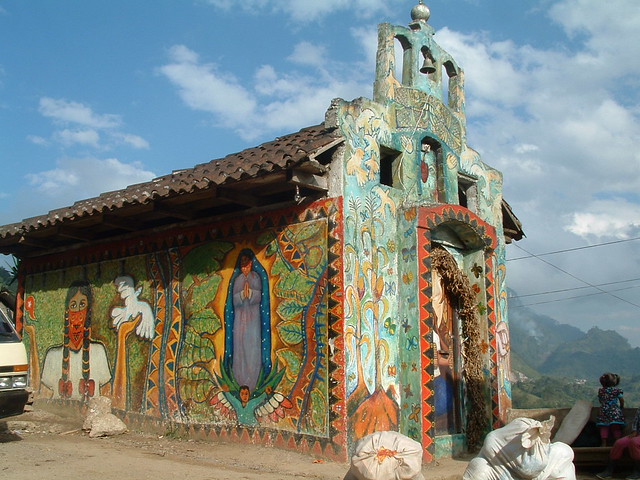

Photo by David Sasaki in Flickr

By Francisco Zepeda

Ph.D. Student in the Cultural Studies Program

When I decided to apply to the Cultural Studies Ph.D., I had mainly two reasons in mind. First, the relevance of culture for understanding social problems, which requires an interdisciplinary approach. Second, the commitment to social change, beyond purely academic purposes.

During my MA in Religious Studies, my research focused on the relationship between religion, social imaginaries, cultural identity, the public sphere, and social problems in Mexico. My different essays on poverty, migration, religious freedom, secularism, and Mexican Social imaginaries led me to discover the importance of culture for analyzing my country’s social problems. The Marxist interpretation situates culture and religion within the ideological superstructure used to maintain the material relations of production, oppressing the poor classes and benefitting capital owners. During my childhood, the Theology of Liberation, a Roman Catholic movement in Latin America developed after the Second Vatican Council, highly influenced my state social environment. Using Marxist approaches, some of them argued that religion has been used in the past as an instrument of oppression and emphasized the necessity of promoting not only spirituality but also liberation from material conditions of oppression, particularly for Indigenous and working classes. Consequently, some of them supported armed conflicts, which in the case of Chiapas, led to the Zapatista Guerrilla in 1994. Following Weber (1920), my interest has been to explore an alternative and complementary approach that analyzes the role of cultural and religious constructs as factors that influence the configuration and performance of political and economic systems. Within this line of thought, my approximation to culture has been through the categories of nations as ‘imagined communities’ (Anderson 1983) and ‘social imaginaries’ (Taylor 2002; 2004).

In my MA Essay, I investigated religious and secular imaginaries’ role in constructing Mexico as a modern country. Specifically, I studied the Constituents’ imaginaries as they appear in the Diary of Debates of the Constituent Congress, which promulgated the country’s current Constitution in 1917. It synthesized the achievements of the first century of Mexico’s independent history and integrated the social conquests of the Revolution. Notwithstanding, due to its anticlerical ideology, the Constituents promulgated a Constitution that included radical anti-religious articles limiting religious freedom. This imposition was contested by large sectors and produced a religious conflict, the Cristero War (1926-1929). Peace was achieved by an agreement between the Catholic Church and President Portes Gil, which is considered a ‘simulation.’ The Constitution’s anti-religious articles would remain, but the Government would not apply them. The ‘simulation’ lasted until the reform of 1992, which moderated the anti-religious character of the Constitution, and created a new legal framework for regulating the relationship between the state and the new religious pluralism. During my Ph.D. I will further and expand this research.

My first months during the Cultural Studies program have exposed me to the complexity of the concept of culture (Bennett et al. 2005), the necessity for epistemic disobedience and decolonial freedom (Ang 2020) or the contradictions that experience people born under imperialism (Hall and Morley 2018). I also realized that my personal struggle to reconcile Marx and Weber’s approaches to culture and religion relates to what Hall and Morley (2018) describe as the two paradigms in Cultural Studies, the culturalist and the structuralist. On the one hand, the culturalist paradigm sees culture as “interwoven with all social practices” and “the activity through which men and women make history” (10). On the other hand, the structuralist paradigm understands culture as ‘ideology,’ either following Marx’s interpretation, which considers culture as a superstructure that served the “dominance of a ruling class over a dominated one,” or following Levi-Strauss and Althusser, who considered culture as “unconscious structures” through which we experience our life (15). Other theoretical concepts such as ‘biopolitics’ and ‘necropolitics’ (Mbembe 2003), ‘crip nationalism’ (Puar 2017), or ‘care work’ (Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018), and the “Scholar Strike Canada” events (“Scholar Strike Canada” 2020) helped me to reinforce my commitment to go beyond academic debates to promoting social change. When human lives are being excluded, dominated, abandoned, destroyed or eliminated, I do not have the right to be indifferent. And because of that, my research regarding culture, religion and social problems in Mexico is not only theoretical.

I want to contribute to the solutions to the social crisis that Mexico is facing. Having experience in different environments, such as the business sector, NGOs and academia, I am convinced of the importance of building bridges. Challenges in Mexico are enormous. Understanding cultural aspects of Mexico’s development is necessary to promote constructive solutions, particularly in a country where many cultures and identities coexist and where most people suffer exclusion and inequality. Also, in the context of the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), a deeper understanding of Mexican social imaginaries may contribute to improving trilateral relationships that may reduce inequalities and promote social and human development within the region.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

Ang, Ien. 2020. “On Cultural Studies, Again.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (3): 285–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877919891732.

Bennett, Tony, Lawrence Grossberg, Meaghan Morris, Raymond Williams, and Tony Bennet, eds. 2005. “New Keywords: A Revised Vocabulary of Culture and Society.” In . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Hall, Stuart, and David Morley. 2018. Essential Essays. Vol. viii. ix vols. Stuart Hall, Selected Writings. Durham: Duke University Press. https://books.scholarsportal.info/en/read?id=/ ebooks/ebooks4/ duke4/2019-05-20/1/9781478002413.

Mbembe, A. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. 2018. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2017. “Crip Nationalism: From Narrative Prosthesis to Disaster Capitalism.” In The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability, 92–123. Anima. Durham: Duke University Press.

“Scholar Strike Canada.” 2020. 2020. https://scholarstrikecanada.ca/.

Taylor, Charles. 2002. “Modern Social Imaginaries.” Public Culture 14 (1): 91–124. http://muse.jhu.edu/article/26276.

———. 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385806.Weber, Max. 1920. Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.